Hot Water: China's Leading Problem

November 29, 2017 | On a flight from Tanzania to Beijing a few years ago, I was surrounded by Chinese workers going home for Spring Festival. None of the passengers spoke any English, and few flight attendants spoke Chinese. The passengers had an improved opinion of me when I helped them translate their health forms, but when I told the attendant they wanted boiling hot water, I became their hero. Once one man got his thermos filled, they all excitedly began passing their thermoses to the overwhelmed stewardess.

It may seem unusual to some Westerners who prefer their water room temperature or colder, but Chinese have preferred boiled water for some time. The custom has roots in traditional Chinese medicine, but it gained popularity during the Chinese Civil War. During that time, both Nationalist and Communist governments encouraged their populations to boil water to prevent the spread of disease. After the Communist takeover, people would deliver hot water to households, filling containers that had been left outside. Today, the Beijing Water Authority agrees: “You can definitely drink the [tap] water. If you are afraid of germs, just boil it. There is no reason to worry.”

Many scientists and watchdogs beg to differ. A Stanford study estimated that a quarter of the Chinese population drinks contaminated water daily, leading to dangerous health complications. The contaminants are toxic chemicals and heavy metals, something that boiling water simply cannot fix. Northern China, a region already plagued by natural water scarcity, is severely affected, with more than 80 percent of underground water considered unsuitable for consumption or even bathing. Villagers in Shanxi province have a higher chance of drinking arsenic-contaminated well water than winning a coin toss.

This problem is not limited to rural areas, either. Scientists recently found that lead levels in Danjiangkou Reservoir, which supplies more than 60 percent of Beijing’s tap water, were 20 times higher than World Health Organization (WHO) safety standards. WHO says that blood lead concentrations of five parts per billion (ppb) can cause cognitive impairment in children; the lead levels recorded at Danjiangkou were over a shocking 200 ppb. For comparison, in 2015, water samples from Flint, Michigan had lead levels of 158 ppb. To make matters worse, Beijing’s 20-year-old pipe network is rusting and riddled with leaks, causing contamination along the way to millions of taps. This does not even consider the urban Chinese, who are digging shallow wells into heavily contaminated aquifers, something the Beijing Water Authority considers “beyond our responsibility.”

Chinese government officials insist that there is no problem, which is understandable, considering the stakes if the true size of the problem were to be acknowledged. There may be public outrage, for example, if people learned that $2.56 billion of the 2015 water pollution budget was not effectively used. There may be widespread instability if people learned about predictions of a massive water shortage by 2030. This does not excuse active government cover-ups and preventing access to care, however. A Human Rights Watch report from 2011 details how numerous officials not only denied the scope of lead pollution, but also prevented residents from receiving blood tests and medical treatment. As China’s water crisis continues to worsen, it is concerning to contemplate how the government may respond.

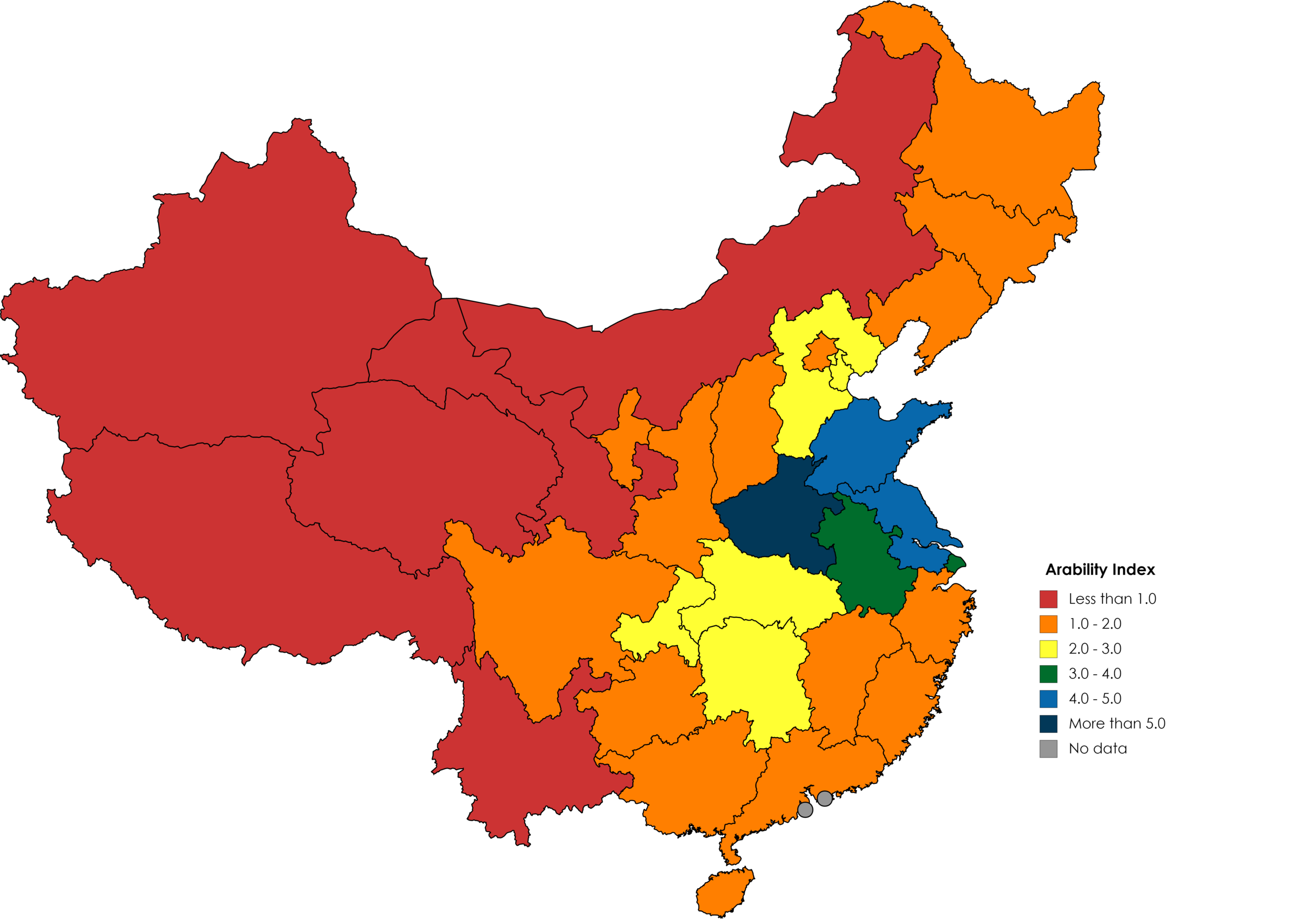

Water pollution is poisoning China’s hegemonic ambitions, not only posing a grave threat to public health, but also to China’s food security. China’s agriculture is already in a precarious position, with seven percent of the world’s arable land supporting 17 percent of the world’s population. The map below shows arability index, which is a measure of how agriculturally productive a province is relative to its size:

The most productive provinces are Henan (dark blue), Shandong (light blue, northern), and Jiangsu (light blue, southern). This concentration of arable land is where the Yellow River meets the Bohai Sea, and is known as the North China Plain. The provinces that constitute the North China Plain have some of the highest population densities in the country.

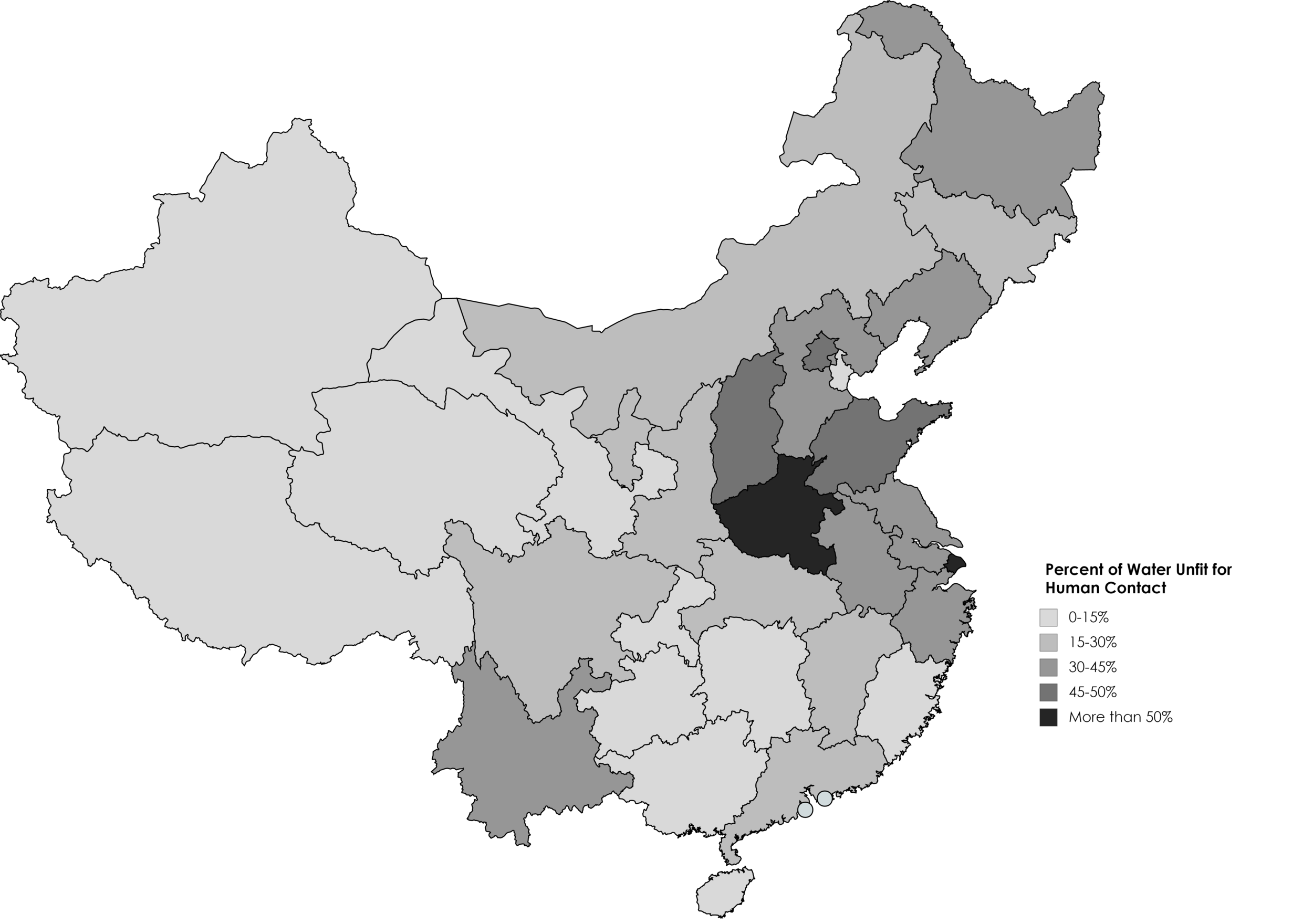

Let’s look at Henan for a moment. Besides agriculture, Henan’s contribution to the Chinese economy mainly comes in the form of construction, leather and fur, and metals. The metal industry, if unchecked, can release heavy metals into the air and water, wreaking havoc on the environment. The tanning process involves the use of many arsenic- and chromium-based compounds, many of which are toxins that can contaminate water supplies if not disposed of properly. The map below shows the percentage of surface water deemed “unfit for human contact” by the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP):

The North China Plain, which supports most of China’s agricultural production, also has the most severe water pollution in the nation. To make matters worse, the MEP has extremely lax environmental standards – even if water is deemed unfit for human contact, it can still be used for agricultural purposes. This means that water that is too dangerous to drink or shower in can hypothetically be used to water crops. Studies have shown that lead is harmful to plants and disrupts their metabolic pathways, which will likely lead to widespread crop failure as water pollution increases in severity and scope. The map below shows the risk to national food production:

A century ago, the Chinese governments identified a risk to public health, raised awareness, and spurred support for drinking boiled water. This shaped national customs and saved lives. As China entered the industrial age, however, the nature of its water woes changed. Boiling water is no longer a guarantee that it is safe to drink, but because they have not been told otherwise, many believe it is. The current Chinese government must galvanize support for clean water once more.

Photo credit: "Pollution-in-china.jpg" by JungleNews for Wikimedia Commons with a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. No changes were made to the original image. Use of this image is not endorsement from its creator.

Map 1: "Arability Index" map created by author using Mapchart. Provincial land area data taken from Wikipedia. Provincial agricultural output data taken from USDA Economic Research Service. Arability index calculated by dividing percent of agricultural production by percent of country’s landmass.

Map 2: "Percent of Water Unfit for Human Contact" map created by author using Mapchart. Water pollution data taken from Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs on November 17, 2018. "Unfit for human contact" defined as Grade IV, Below Grade V, and Grade V water. "Fit for human contact" defined as Black and Smelly, Grade I, Grade II, and Grade III water. Definition adapted from "Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water," published by the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection.

Map 3: "Risk to Agriculture Production" map created by author using Mapchart. Risk factor determined by multiplying arability index by dirty water (Grades IV-V+)-clean water (Grades I-III) ratio.

The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect the views of other Arbitror contributors or of Arbitror itself.